In this blog post, we are delving into World Models (Ha et al., 2018)[1] a recent model based reinforcement learning paper that achieves surprisingly good performance on the challenging CarRacing-v0 environment.

Along with a short summary of the paper, we provide a pytorch implementation , as well as additional experiments on the importance of the recurrent network in the training process.

Summary of World Models

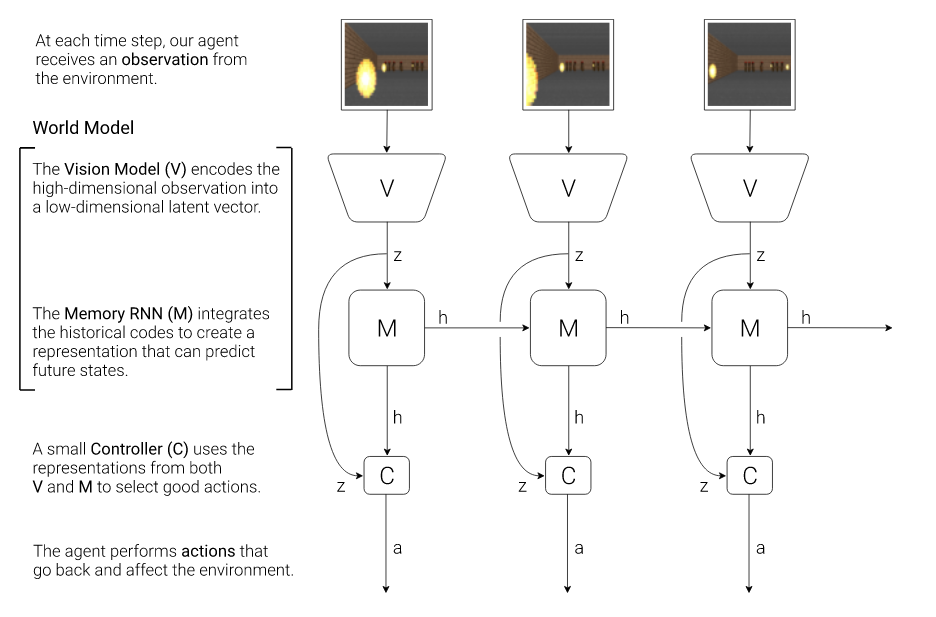

World Models introduces a model-based approach to reinforcement learning. It revolves around a three part model, comprised of:

- A Variational Auto-Encoder (VAE, Kingma et al., 2014)[2], a generative model, who learns both an encoder and a decoder. The encoder’s task is to compress the input images into a compact latent representation. The decoder’s task is to recover the original image from the latent representation.

- A Mixture-Density Recurrent Network (MDN-RNN, Graves, 2013)[3], trained to predict the latent encoding of the next frame given past latent encodings and actions. The mixture-density network outputs a Gaussian mixture for predicting the distribution density of the next observation.

- A simple linear Controller (C). It takes as inputs both the latent encoding of the current frame and the hidden state of the MDN-RNN given past latents and actions and outputs an action. It is trained to maximize the cumulated reward using the Covariance-Matrix Adaptation Evolution-Strategy (CMA-ES, Hansen, 2006)[4], a generic black box optimization algorithm.

Below is a figure from the original paper explaining the architecture.

On a given environment, the model is trained sequentially as follows:

- Sample randomly generated rollouts from a well suited random policy.

- Train the VAE on images drawn from the rollouts.

- Train the MDN-RNN on the rollouts encoded using the encoder of the VAE. To reduce computational load, we trained the MDN-RNN on fixed size subsequences of the rollouts.

- Train the controller while interacting with the environment using CMA-ES. At each time step, the controller takes as input both the encoded current frame and the recurrent state of the MDN-RNN, which contains information about all previous frames and actions.

Alternatively, if the MDN-RNN is good enough at modelling the environment, the controller can be trained directly on simulated rollouts in the dreamt environment.

Reproducibility on the CarRacing environment

On the CarRacing-v0 environment, results were reproducible with relative ease. We were pleasantly surprised to observe that the model achieved good results on the first try, relatively to the usual reproducibility standards of deep reinforcement learning algorithms [5, 6]. Our own implementation reached a best score of 860, below the 906 reported in the paper, but much better than the second best benchmark reported which is around 780. We believe the gap in the results is related to our reduced computational power, resulting in tamed down hyperparameters for CMA-ES compared to those used in the paper. Gifs displaying the behavior of our best trained model are provided below.

Additional experiments

We wanted to test the impact of the MDRNN on the results. Indeed, we observed during training that the model was rapidly learning the easy part of the dynamic, but mostly failed to account for long term effects and multimodality.

In the original paper, the authors compare their results with a model without the MDRNN, and obtain the following scores :

| Method | Average score |

|---|---|

| Full World Models (Ha et al., 2018)[1] | 906 ± 21 |

| without MDRNN (Ha et al., 2018)[1] | 632 ± 251 |

We did an additional experiment and tested the full world model architecture without training the MDRNN, keeping its random initial weights. We obtained the following results :

| Method | Average score |

|---|---|

| With a trained MDRNN (Ours) | 860 ± 120 |

| With an untrained MDRNN (Ours) | 870 ± 120 |

We display the behavior of our best trained model with an untrained MDRNN below.

It seems that the training of the MDRNN does not improve the performance. Our interpretation of this phenomenon is that even if the recurrent model is not able to predict the next state of the environment, its recurrent state still contains some crucial information on the environment dynamic. Without a recurrent model, first-order information such as the velocity of the car is absent from individual frames, and consequently from latent codes. Therefore, strategies learnt without the MDRNN cannot use such information. Apparently, even a random MDRNN still holds some useful temporal information, and that it is enough to learn a good strategy on this problem.

Conclusion

We reproduced the paper “World Models” on the CarRacing environment, and made some additional experiments. Overall, our conclusions are twofold:

-

The results were easy to reproduce. It probably means that the method on this problem does not only achieve high performance but is also very stable. This is an important remark for a deep reinforcement learning method.

-

On the CarRacing-v0 environment, it seems that the recurrent network only serves as a recurrent reservoir, enabling access to crucial higher order information, such as velocity or acceleration. This observation needs some perspective, it comes with several interrogations and remarks:

- (Ha et al. 2018) reports good results when training in the simulated environment on the VizDoom task. Without a trained recurrent forward model, we cannot expect to obtain such performance.

- On CarRacing-v0, the untrained MDRNN already obtains near optimal results. Is the task sufficiently easy to alleviate the need for a good recurrent forward model?

- Learning a good model of a high dimensional environment is hard. It is notably difficult to obtain coherent multi modal behaviors on long time ranges (i.e. predicting two futures, one where the next turn is a right turn, the other where it is a left turn). Visually, despite the latent gaussian mixture model, our model doesn’t seem to overcome this difficulty. Is proper handling of multi modal behaviors key to leveraging the usefulness of a model of the world?

Authors

- Corentin Tallec - ctallec

- Léonard Blier - leonardblier

- Diviyan Kalainathan - diviyan-kalainathan

License

This project is licensed under the MIT License - see the LICENSE.md file for details

References

[1] Ha, D. and Schmidhuber, J. World Models, 2018

[2] Kingma, D., Auto-Encoding Variational Bayes, 2014

[3] Graves, A., Generating Sequences With Recurrent Neural Networks, 2013

[4] Hansen, N., The CMA evolution strategy: a comparing review, 2006

[5] Irpan, A., Deep Reinforcement Learning Doesn’t Work Yet, 2018

[6] Henderson, P. Islam, R. Bachman, P. Pineau, J. Precup, D. Meger, D., Deep Reinforcement Learning that Matters, 2017